I don’t come to you with my problems, do I?

A somewhat eccentric role model for managers

Introducing himself to Bob Dylan at a party, Peter Grant extended his hand and said, “Hi. I’m Peter Grant, manager of Led Zeppelin.”

Dylan looked at him and said, “I don’t come to you with my problems, do I?” then turned and walked away.

This famous anecdote says a lot about Dylan’s dyspeptic personality (Dylan was our Kanye, but with a sense of humor), but it indicates more, and better, I think, about why Peter Grant was a great manager.

Peter Grant

Grant was a former South London wrestler who became one of the most powerful men in the music industry. The formidable 6 foot, 5 inch, ‘Genghis Khan of Rock’ struck fear into the hearts of anyone foolish enough to try to rip off one of his bands.

Across a long career, Grant managed the Yardbirds, Bad Company, Bo Diddley, The Everly Brothers, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent, and the Animals, but his reputation was cemented in rock history with Led Zeppelin.

There were many rough edges to this ex-wrestler (who once beat up a security guard who mistakenly cuffed his son), including years of drug abuse and depression when John Bonham (Led Zeppelin’s drummer) died of alcohol abuse.

But, for now, let’s focus on Grant’s positive attributes, the ones we’d like to see in all our managers.

A great manager is still a fan

Grant, like most successful band managers, loved the music, the band that made the music, and the music business. Ahmet Ertegun, the president of Atlantic Records (Led Zeppelin’s label), said, “Peter put his artists on a pedestal. Their word, their wish, their music, that was the most important thing in his life.”

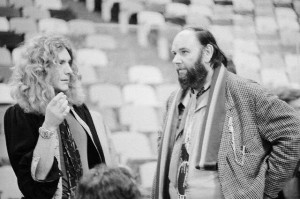

You can tell just by looking at any picture of him standing next to his band. In most he wears an ear-to-ear grin that says, “Oh my god. I’m standing next to a rock star.”

That’s after 30 years of standing next to rock stars.

You see the same when Irving Azov stood next to the Eagles, when Brian Epstein stood next to the Beatles, or when Richard Branson stood next to Mike Oldfield. The most un-wowable are wowed by their charges.

It’s drunk love for both producer and product.

I’ve found the same with the great band managers I’ve worked with (in rock bands or a cube farms). I’ll never forget looking over at Don Rose, the manager of a band I was in for many years, running a lighting footboard when the lighting man didn’t show at some forgettable gig in Massachusetts. He looked giddy as a farm boy, knees bobbing up and down to the music. He was just as giddy when working with Morphine, Frank Zappa, and David Bowie years later.

I rarely see this kind of fandom in managers in business today. If a manager in a company is unlucky enough to get photographed with his or her team, they usually look like someone just passed wind.

And, as exciting as our world is these days, many managers I see don’t really love the end product. Amidst the metrics and analytics charts that float around most offices, I find, at least in the software industry, managers rarely enjoy the actual software their team creates, which is downright weird in a world where teenagers talk about apps like we used to talk about albums.

Question for managers: Are you a fan of your team, their products, and the business you are in?

Great managers create a wall around the team so the team can focus

John Paul Jones, the bass player, keyboardist, and reticent musical genius behind Led Zeppelin said, “Peter trusted us to get the music together, and then just kept everybody else away, making sure we had the space to do whatever we wanted without interference from anybody–press, record company, promoters. He only had us [as clients] and reckoned that if we were going to do good, then he would do good. He always believed that we would be hugely successful and people became afraid not to go along with his terms in case they missed out.”

Grant used his intimidating presence to maintain order and to keep his charges safe and focused on their expertise. When a bootlegger or unauthorized photographer crawled into view, they usually found themselves at the butt of his pointer finger and a four-letter assault (see The Song Remains the Same for a loud reminder).

Despite his enthusiasm, Grant was never tempted to interfere with the band’s records or stage act. He left the music entirely in the hands of the musicians. Imagine helping John Bonham nuance When the Levy Breaks or giving Jimmy Page pointers on fingering Dazed and Confused.

But many managers do just that. In some businesses today, it seems to be a badge of honor for managers swoop in last minute with bright ideas, as if the team needed the inspiration, just doesn’t get it, or has no craft of their own.

If the end product is not the manager’s concern, they often think it’s a good idea to dictate the tools, estimation, or planning for the work they ultimately have no role in delivering.

Question for managers: Are you protecting your team and allowing them to focus and learn from their mistakes and successes?

(Robert Plant and Peter Grant. Courtesy David Zoso)

A great manager tolerates (and even encourages) irregular personalities

There are hundreds of John Bonham anecdotes out there. One of the most famous is the day Bonham and his drinking partner Stan Webb left a Chrysalis Records executive bound from head to foot in duct tape on Oxford Street in London. Then, hours later and still drunk, Bonham and Webb rented robes from a costume shop, borrowed a Rolls-Royce Phantom Six, and drove to the Mayfair Hotel where they posed as Arabian princes, booked themselves into the Maharajah suite, ordered fifty steaks, then wallpapered the suite with them.

Grant made a career of dealing with, paying for, and sometimes promoting those indulgences (you may sniff, but are probably glued to worse on Facebook), corralling them to the best of his abilities.

Grant wasn’t the only one, of course. Andrew Loog Oldham, manager of the Rolling Stones, created and nurtured the “bad boy” perception of the Stones as an alternative to The Beatles. Brian Epstein, the Beatles’ manager, dressed the boys in mohair suits and took them to a barber on Lord Street, a photographer forever in tow.

Accepting and encouraging peccadillos is part of winning trust with eccentrics. If Eminem wants a jar of banana pepper rings and 6 Lunchables (3 turkeys and 3 ham with cheese) in his dressing room, then that’s what he gets. If Katy Perry says no carnations, then no carnations. If the Rolling Stones wants the hotel bar to stay open all night and written instructions on how to use the gd DVR, then that’s a small price to pay for the world’s greatest rhythm section.

What do current managers in many companies do instead? They encourage sameness. And, if that doesn’t materialize, they pester HR to hire a ‘business coach’ to sand down the weirdo’s raw edges. If push comes to shove, they can always encourage the brilliant guy to work from home.

Caveat: There’s a limit to eccentricity, of course, and many rock band (and some technologist) antics go beyond the pale. In any business, when a team member’s eccentricities slows the team, puts others or themselves in danger, or just doesn’t bring any value, then the manager has to put a stop to it (which Grant did not do, to the ultimate demise of Led Zeppelin).

Question for managers: Are you supporting, and maybe even encouraging, the eccentrics (within limits)?

A great manager gets the team to (and often away from) the gig, regardless

Peter Grant once rented a train to get the band to a gig when all flights were grounded by a storm. He once purchased a fleet of limos with cash on the spot and drove himself to get his band through a union dispute. He once taped Jimmy Page’s finger with duct tape after Page caught his ring finger in a train door. He once taped Gene Vincent’s leg to mic stand after he sprained it in a drunken brawl before going on stage (tip: great managers always have duct tape). He once rolled Little Richard in a Persian rug and carried him to the Lyceum when Little Richard ‘just didn’t want to go on.’

“Grant was a roadie at heart,” says writer Johnny Rogan, the author of Starmakers And Svengalis. “Some managers sit behind desks, dealing with paperwork and pay others to be on the road with their bands. Grant wasn’t like that. He loved the road.” Grant was at every show, prowling around backstage, sorting out problems, making sure the band got onstage, and making sure the band got paid.

Can you imagine this level of involvement from managers today? I find many are not aware when their team members don’t show up. If they do, the first gambit is to kibitz about millennials’ lack of dedication instead of cajoling, bribing, or wrestling them to the finish line (or taping their leg to a mic stand).

Question for managers: How far would you go to get your team to the finish line?

A great manager always makes sure his/her team is successful

Grant has been described as “one of the shrewdest and most ruthless managers in rock history”. In 1968, Grant finessed Atlantic Records into coughing up a then unprecedented $200,000 advance for Zeppelin’s five-year recording contract, plus the highest royalty rate ever negotiated for a band (5X that of The Beatles). This approach, even now, 40 years and Spotify later, has paid off big time for the remaining members of the band, and for Atlantic Records.

Grant is reported to have secured 90% of gate money from concerts performed by the band. An unprecedented feat. By taking this approach he set a new standard for artist management, “Single-handedly pioneer[ing] the shift of power from the agents and promoters to the artists and management themselves,” said Rogan.

Grant watched over every penny for his team, and didn’t let them go on stage unless they first got their fair share.

What do many managers in business do? Unfortunately, many don’t have the courage to take tickets at a ballet, let alone demand more for the team from pinchpenny executives. Instead, many spend their time angling to make their teams’ successes look like their own, expressing their appreciation with a 5% a year raise, and preparing a half-hearted invocation for a pizza party. If big dollars ultimately do get distributed, they tend to go to agencies with hip sales people who leave inexperienced college grads behind to actually do the work.

Question to managers: Are you doing everything you can to make sure your experienced teams are getting their fair share?

There are Always Bad Apples, Of Course

For every good manager–in any business–there are ten bad ones, if not more. Bad apples are as rampant in the music business as anywhere else, but they seem more flamboyantly evil.

Lou Pearlman, for example, the manager of the Backstreet Boys and NSYNC, was arrested in 2007 for embezzling more than $300 million from investors with a televangelist’s ambisexual flair.

Pearlman is certainly not the only one. Brian Epstein did a terrible job managing the Beatles rights with far less intentional malice than Pearlman. A 1966 audit showed that EMI owed The Beatles in excess of $30 million in royalties that they sold in “under the table” deals during the time before a new contract was signed. This loss could have been avoided had Epstein had hired competent advisers.

Fortunately history shows bad apples usually get what they deserve, living out their remaining days in double-wides littered with beer cans, drug addled, or in jail.

The good apples are usually well rewarded, thankfully. Paul McGuinness, who has managed U2 throughout their entire career, by all reports, is open, honest, courteous, and transparent with the band’s financial dealings. Whatever you think about the band itself, you have to hand it to McGuinness for running a shrewd, long-term business that tries, valiantly, to do the right thing.

Who’s Next

Lots has changed in the world of management in the past ten years. It’s a confusing time for managers confronted with small, self-directed teams (not unlike rock bands). Managers no longer direct the process or the product. Managers are not critiquing code or creative. They are not choosing the next change or feature, and sometimes not even influencing the strategic direction of the product.

The customer is (well, at least the product owner is. But we’ll fix that soon).

We still need managers. Great managers. Managers who live to make sure their teams have access to the right audience, the right venues. Managers who make sure the team has the right equipment and the time and space to innovate and deliver quality. Managers who manage the gray area around teams, making sure all the dirty business is taken care of.

Managers who keep the team’s problems to themselves.

So, throw your devil horns in the air, Eugene. The band is back in town and waiting for you to bring the limo around.

(Source: http://lethereberock.forum-actif.net/)

(Coda: Grant kicked his drug and depression problems and died a happy, respected, and rich collector of antiques).

Related Posts

-

Nobody wants to imagine the fruits of their labor dying on t...Sep 21, 2016 / 0 comments

-

Catching someone doing something well that they enjoy doing�...Dec 25, 2018 / 0 comments

-

t’s not that hard to figure out when you are working with ...Oct 08, 2018 / 0 comments

Categories

Recent Posts

CONTACT INFO

Welcome to Coral Mountain Consulting, a Deliverse company. We are glad you found us. If you need to contact us, please call or email Barc directly.

Phone: 1-(626) 644-3857

Office: 2122 New York Drive, Altadena, CA 91001